I am impressed with Thomas Jefferson's agrarian state. I believe we in America and the world can accomplish a similar society of communal quasifarmers in a way using advanced technology, transportation, and communications. He's also quite a man, Thomas Jefferson. Observe:

Thomas Jefferson: On Liberty and Power

International Politics

Published in The Freeman: Ideas on Liberty - April 1993

by Clarence B. Carson

It is doubtful that Thomas Jefferson could have been elected President in the twentieth century. It is almost equally doubtful that he could have been elected to that high office at any time past 1850. Now I do not draw these conclusions simply because, as we say, times change, and any person thrown suddenly into another era would be more or less out of place and unsuited to positions of power and prestige in the later era. It is rather that Jefferson did not have the temperament, character, and turn of mind to have won election in the later era.

The Man

Jefferson shrank from public debate as a young child does from going into the darkness alone. He avoided, so far as possible, all occasions for public speaking. He disliked pomp, ceremony, confrontations, and heated discourse. As President, he preferred written opinions from his department heads rather than to convene cabinet meetings in an attempt to reach conclusions. He was tall, gangly, freckled, sandy-haired, and some thought they detected a sneakiness about him. For this latter reason, especially, he would probably have been a disaster on television, where openness and straightforward honesty of appearance is essential, though actors can feign such looks with ease, while honest men with a squint might be thought scoundrels. Some thought Jefferson was being overly anxious for popular approval when he did not speak out on controversial matters. The truth may be otherwise; Jefferson loved the truth too much to see it traded casually in the marketplace.

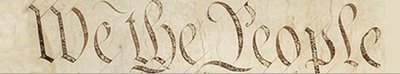

In any case, Jefferson was retiring and what we would call “cerebral.” Possibly no man since Aristotle took more pleasure in observing, recording, and classifying or describing natural phenomena than did Jefferson. Indeed, when time permitted, he filled notebook after notebook with such observations. Jefferson had an active and innovative interest in every intellectual pursuit and activity of his day. He carried on a vigorous correspondence with European and American philosophers and scientists throughout much of his life. His talents were varied and his interests universal. He was trained in the law and admitted to the bar, served in the colonial legislature of Virginia and the Second Continental Congress, drafted the Declaration of Independence, was elected governor of Virginia, was a prolific writer, served as Minister to France, was first Secretary of State of the United States, and was elected second Vice President and third President of his country.

As if all that were not enough, he was a gentleman farmer, a manager of a large estate, a scientist, an inventor, and an architect. Of his inventions, “He invented a hempbeater, worked out a formula for a mold board plow . . . . devised a leather buggy, a swivel chair, and a dumbwaiter . . . . He was constantly studying new plows, steam engines, metronomes, thermometers, elevators, and the like, as well as the processing of butters and cheeses. He wrote a long essay for Congress on standards of weights and measures in the United States . . . . [and] conceived the American decimal system of coinage . . . .”[1]

Indeed, books could be written, and many have been, on Jefferson’s life and attainments. Several of his contributions, each on its own, might have earned him a secure place in American history. Almost certainly his authorship of the Declaration of Independence would have made him a fixture in the firmament of the Founders. His Virginia Bill of Religious Liberty was a classic statement even before it was adopted by that legislature. His two terms as President by themselves have earned him a place among America’s Ten Greatest Presidents.[2] His efforts in founding the Jeffersonian Republican Party would surely have been remembered, as would his architectural contributions for the University of Virginia, the magnificent concept of Monticello, and his background aid for the layout of Washington, D.C. Much more could be named, but surely his eminence has long since been established.

Jefferson himself wanted to be remembered for his authorship of the Declaration of Independence, the Virginia Bill of Religious Liberty, and his contribution to the founding of the University of Virginia. These are indeed enduring monuments, though his First Inaugural Address is no less one. Yet there is something else that he did for which he most needs to be remembered in our time. Jefferson was a vigorous and instructive advocate of the constitutional dispersion of powers of government—the separation of powers within the United States government and their dispersion between the central and state governments. He championed this aspect of the Constitution because it limited government, and limited government was essential to individual liberty.

Defender of Liberty

It is well known, of course, that Thomas Jefferson was an outspoken advocate of individual liberty. He defined it this way: “Of liberty then I would say that in the whole plenitude of its extent, it is unobstructed action according to our will, but rightful liberty is unobstructed action according to our will within limits drawn around us by the equal rights of others.”[3] Moreover, Jefferson professed a passionate attachment to liberty. He wrote to Dr. Benjamin Rush that he had “sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.”[4] His belief in liberty was based in the natural rights doctrine, itself grounded in natural law theory. Most proponents of natural rights maintained that natural rights were altered and reduced when man entered society. Jefferson, by contrast, argued that “the idea is quite unfounded that on entering into society we give up any natural right.”[5] In any case, Jefferson was a vigorous advocate of individual liberty.

There should be no doubt, either, that Jefferson believed that government was the greatest, if not only, threat to individual liberty. He wrote that “The natural progress of things is for liberty to yield and government to gain ground.”[6] This is so because those who gain positions of power tend always to extend the bounds of it. Power must always be constrained or limited else it will increase to the level that it will be despotic. Jefferson wrote to Judge Spencer Roane in 1819, “It should be remembered, as an axiom of eternal truth in politics, that whatever power in any government is independent, is absolute also. . . .”[7] With this principle of necessary limitation in mind, Jefferson declared “that a bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular; and what no just government should refuse, or rest upon inference.”[8]

Nor did his many years in government service assuage his fears of government nor lead him to view it as any less a threat to liberty. If anything, it confirmed him in his earlier beliefs about not entrusting overmuch to those in power. But it was not so much Jefferson’s tenacious attachment to liberty nor especially his fear of government power that set him apart from many of his contemporaries. Most American leaders of the founding era expressed similar beliefs. It was also widely believed that the powers of government should be separated and balanced so that men in power, in their struggle with others for power, would be constrained and limited in their exercise of power. This was generally believed to be the necessary condition for the continuation of liberty.

Most of Jefferson’s contemporaries subscribed to the idea that the powers of government should be dispersed—at least so far as to divide them among the three branches. Many became persuaded, too, that dividing the powers of government between the general and state governments was a good thing. But few, if any, saw as clearly as Jefferson did how much effort had to be put into making such a system work and how far the effort had to be carried.

If the system of checks and balances is to work, he thought, it would be because those entrusted with power used their imaginations, wills, and determination to protect their interests and assert their prerogatives. Checks and balances entail tension, an ongoing and, above all, unresolved tension, and men are usually disinclined to live with unresolved tensions. The natural inclination is to establish some authority who, or which, has the assignment to settle the issues, once and for all, and resolve the tension. Jefferson understood more clearly than anyone else ever has, or at least discussed it more clearly, that the resolution of these tensions—arising from different claims to power among the branches or between the states and the United States—would be to remove the checks and balances...